Interview: Tracking the Ugandan Election Through the Internet Blackout

January 21, 2021 · 7 min read

-

VoxCroft COO

The recent Ugandan election sparked global interest, as Robert Kyagulanyi Ssentamu, known by his stage name Bobi Wine, mobilised his substantial social media following to garner support from the youth against the incumbent president. Bobi Wine’s célébrité pulled international interest in the controversial election, which was marred by deadly protests, the shutting down of the Internet, and the military-enforced house arrest of Bobi Wine. VoxCroft analyst Sarah-Leah Pimentel has experience covering dozens of African elections, and lends her insights on the elections gathered through Open-Source Intelligence (Read our post on what Open-Source Intelligence is here.)

Bobi Wine not pulling punches with his song "Ballot or Bullet" launched as part of his failed presidential campaign.

Fred: The Internet went down. Why was this done? Is this typical for Ugandan Elections?

Sarah-Leah: Yoweri Museveni, the Ugandan president, has done this before. The Internet was shut down in the 2016 election too. The official reasons given are for national security, especially given the riots during the election campaign in November. But effectively it shuts down any conversation that is not directly sanctioned by the government. In addition to this, Museveni’s main contender, Bobi Wine, has a very large following on social media. So shutting down the Internet prevents Bobi Wine from speaking to his supporters.

However, we cannot see the Internet shutdown in isolation. This shutdown comes in the context of an erosion of democratic principles. Only five of the US election observers received accreditation, causing the US to cancel its observer mission. The EU also did not send observers, saying that conditions were not in place for free and fair elections. Four in-country NGOs that worked on voter education and monitorial activities had their bank accounts frozen. Some foreign journalists did not get visas to report on the election.

This paints a far more worrying picture of a regime that seeks to make it difficult to communicate any information about the election — from voter turnout, irregularities, violence, police activity. In this information vacuum, there is very little to counter the government-sanctioned version of events.

Fred: Did the shutdown of the Internet have an impact on the election?

Sarah-Leah: Of course, it puts every part of the election into question. At a press conference with the Electoral Commission, a journalist asked how results from polling stations would be communicated to the official tally center in Kampala without the Internet. The Commission noted that they did not need the Internet to collate the votes. But it raises several questions: do we know that all the polling station results were counted? Were ballot boxes stolen? Was there ballot stuffing? The job of observers is to report irregularities, but if they have no means by which to communicate these incidents, it casts doubt on the election — which has already happened.

Bobi Wine’s supporters are saying that the election was stolen from him. Maybe it was, maybe it wasn’t. But unless there is information and evidence that contradicts the official narrative, we will never know.

Fred: How did you manage to gather intelligence with the Internet down?

Sarah-Leah: Lack of information is also information. It tells us about the mood in the country and possibly concerns from the authorities about their confidence regarding their position and the need to employ heavy-handed means to guarantee the desired results.

The Internet going down was not a surprise. So we made contingencies. When Internet traffic is low, it’s far easier to find isolated voices. This helped. We also tapped into secondary sources, that is regional and international sources reporting on the election. Their lack of information confirmed to us that we were not “missing” anything that might be available..

We started with what we were able to find. Although all online news sources were down, the state-owned broadcaster broadcast on YouTube about twice a day. We observed that this station provided very few updates from polling stations on the day, but from this we were able to learn that voting started late in many places and there were problems with the biometric voting machines, signaling that the election was not running as smoothly as planned, but the station was at pains to say that people had turned out in large numbers and voting was peaceful.

We found a Ugandan journalist who was able to post on his Twitter account (we later found out that he sent text messages to a friend in Kenya who posted the information to his Twitter account). His posts were few and far between but gave an indication as to what Ugandans inside the country were listening to on the radio. From him we learned that security was extremely tight around Bobi Wine’s house and his supporters arrested, and raided the independent observer center. This signalled that the state broadcaster’s information was not the whole story.

We have a contact in Uganda who also sent through a daily text message with the main stories being reported on the country’s many radio stations.

Fred: The current president called for the shutdown of social media accounts of the opposition. Is this typical? Do you think this followed from the US shutdown of former President Trump’s account? Was there any fallout from this?

Sarah-Leah: I think the shutting down of social media accounts signals a very interesting development in how communities consume and share information but also the role that social media platforms are playing in shaping these conversations.

The rationale for shutting down Trump’s Twitter account is that he was inciting people to violence. But it is part of a far larger conversation about what constitutes news, fake news, alternative news, what is true and what is not. And it will be very interesting to see how these trends develop.

However, Museveni had asked Google to shutdown anti-government and pro-Bobi Wine YouTube accounts back in December. This was before Twitter shutdown the former US president’s account. The accounts did not get shut down.

However, just a few days to the election, Facebook reportedly deactivated hundreds of accounts of officials from the Ministry of Information and pro-government entities. The reasons given is that they were engaged in “coordinated unauthentic behaviour” — which basically means bot activity. Museveni retaliated by blocking access to Facebook in the country.

I think the fallout of this is still to be seen. But we must remember that Uganda has never had a great relationship with social media. In 2018, the government implemented a social media tax, which essentially means that blog owners had to pay a tax to have a blog or website. Social media users are also charged a flat rate tax every time they log onto social media or use web-based money transfer platforms. The effect of this is to try and keep people off the Internet, to stop them “gossiping” apparently.

Fred: Was this election typical for Africa?

Sarah-Leah: Several African countries have been known to shut down the Internet, or at the very least reduce Internet speeds during elections. Tanzania restricted access to the Internet and social media during its election in 2020. Ethiopia also shut down the Internet during the unrest that lasted nearly a month last year. Zimbabwe, Togo, Burundi, Chad, Mali, and Guinea have also had shutdowns or throttling of the Internet in the past year.

An article by the BBC shows that the decision by governments in Africa to curtail Internet access during crises has been on the increase in the last four years.

Fred: Did Bobi Wine's social media following affect his performance in this election?

Sarah-Leah: Yes and no. Before becoming a politician, Bobi Wine was a popular singer. He entered politics using the image of the guy from the “ghetto” who represents young, disenfranchised, poor, urban dwellers and his popularity has increased since he first entered the political scene five or six years ago. This already made him appealing to new and younger voters.

Fighting for the hearts and minds of the youth with music.

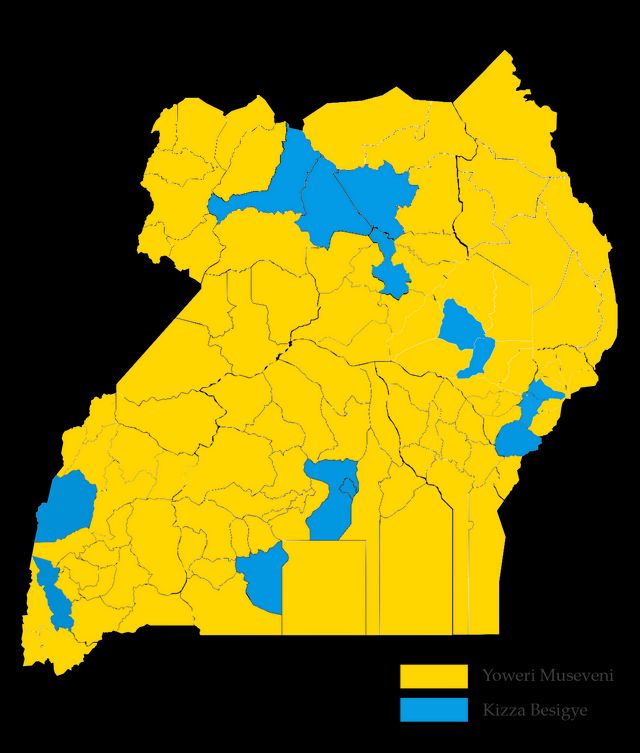

But tied to this is that the official opposition — Forum for Democratic Change — made a decision not to run its four-time presidential contender in this election (Kizza Besigye, who has a long political history doing battle against Museveni). The replacement, Patrick Amuriat Oboi, was targeted by police almost as frequently as Bobi Wine during the election campaign, where both men were arrested several times. But in many ways, Amuriat was an unknown coefficient and it is possible that traditional FDC voters put their vote on Bobi Wine in this election, feeling that they were backing the stronger candidate.

And we cannot discount the fact that Museveni is still widely popular, especially among older, rural voters. He represents peace and stability after the violence of the Idi Amin regime and Milton Obote. Bobi Wine and his ilk represent anger with the status quo, which also frightens many voters.

In several meetings with the youth, they challenged me to do the #Jerusalemachallenge. When I consulted, I was told it's a popular song by South African stars. Of course, I would have loved to dance to my own "Another Rap" but due to the popular demand, I concede. pic.twitter.com/EnxQHrRDDk

— Yoweri K Museveni (@KagutaMuseveni) January 11, 2021

Museveni going out of his comfort zone to attempt to appeal to the youth.

Q: Do you think the global attention on the election made a difference on the election?

Sarah-Leah: Well, Museveni definitely tried to use it in his favor! The US has issued numerous warnings about the erosion of democracy. Museveni and other government officials have said on numerous occasions that Bobi Wine is funded by “foreign agents.” Some have gone so far as to finger the US specifically, especially after it was discovered that Bobi Wine had sent his family to the US for fear of reprisals in the aftermath of the election.

And this fits into Museveni’s wider narrative and clear pan-Africanism, which is that of “African solutions to African problems.” He sees any foreign comments about the state of his country as interference on the part of the international community.

But no, I don’t think that the attention of the international community made a difference to the results. Museveni was always going to win, whether legitimately or not. He has the support of the army. He has a massive state apparatus at his service. He successfully persuaded the Supreme Court to do away with calls for an age limit on the presidency. He had every intention of staying in power and will now work to ensure that his position is entrenched.

Fred: Any other interesting observations around this election?

Sarah-Leah: What will be interesting to watch is the results of the parliamentary election. There are indications that the National Resistance Party has lost MPs in this election.

Bobi Wine on his own as the runner-up to the election holds no position in the Ugandan Government. But if his NUP party can increase the number of seats it holds in Parliament, it will be interesting to see how that will influence political life over the next five years.